Fed Officials Test New Argument For Tightening: Protect The Poor

Discussion puts Fed in spotlight as inequality debate widens; Recent studies find contractionary policy often is regressive.

By Matthew Boesler

Bloomberg

Bloomberg

May 15, 2017

To protect the poorest Americans, should central bankers raise interest rates faster?

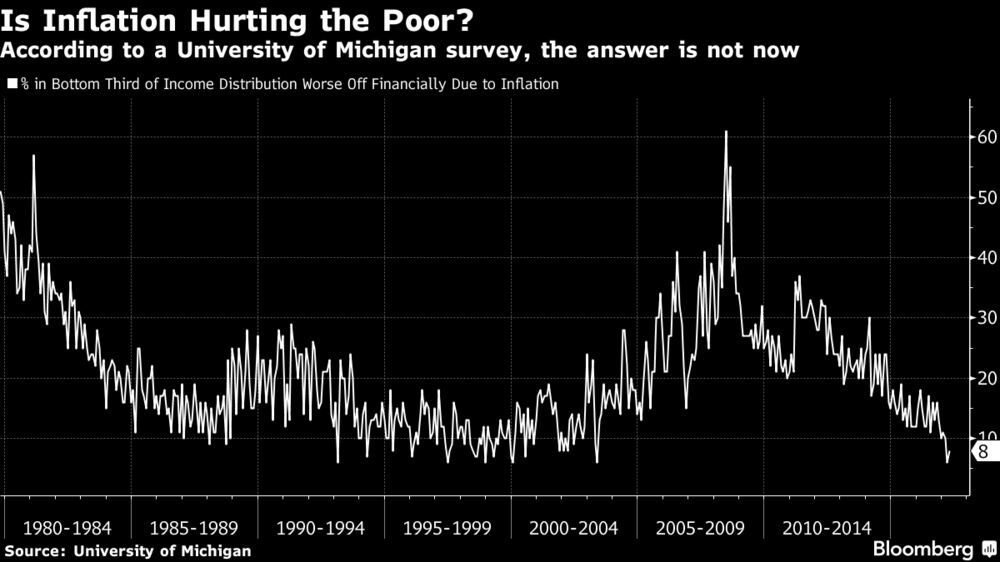

At least one of them is making that argument. During a speech last month, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City President Esther George said she was “not as enthusiastic or encouraged as some when I see inflation moving higher” because “inflation is a tax and those least able to afford it generally suffer the most.”

She was referring in particular to rental inflation, which she said could continue rising if the Fed doesn’t take steps to tighten monetary conditions. And while the idea of inflation as a tax that hits the poor the hardest is not a new one, its role in the current debate over what to do with interest rates marks a bit of a twist from recent years.

Widening disparities in income and wealth have over the past several years permeated national politics and helped fuel the rise of populist movements around the developed world. Against this backdrop, there has been a growing body of research, some of it produced by economists at central banks, backing the idea that easier monetary policy tends to be more progressive.

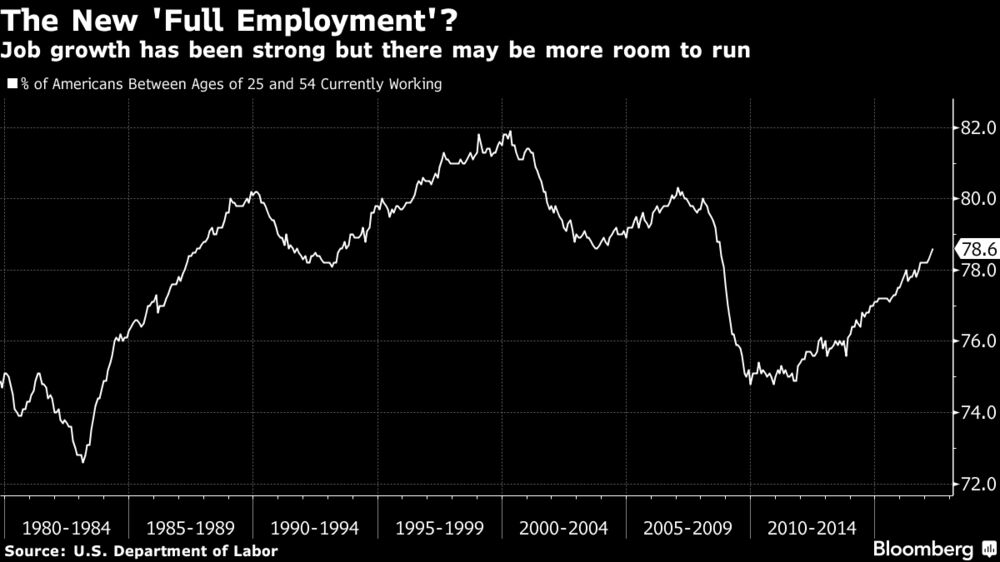

That work, set against the notion that a stricter approach toward containing inflation has the best interests of the lowest-income members of society at heart, is thrusting Fed policy makers toward the center of a debate they usually like to leave to politicians. It’s becoming more contentious as Fed officials seek to declare victory on their goal of maximum employment even while the percentage of prime working-age Americans who currently have jobs is still nowhere close to the peaks of the previous two economic expansions.

To protect the poorest Americans, should central bankers raise interest rates faster?

At least one of them is making that argument. During a speech last month, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City President Esther George said she was “not as enthusiastic or encouraged as some when I see inflation moving higher” because “inflation is a tax and those least able to afford it generally suffer the most.”

She was referring in particular to rental inflation, which she said could continue rising if the Fed doesn’t take steps to tighten monetary conditions. And while the idea of inflation as a tax that hits the poor the hardest is not a new one, its role in the current debate over what to do with interest rates marks a bit of a twist from recent years.

Widening disparities in income and wealth have over the past several years permeated national politics and helped fuel the rise of populist movements around the developed world. Against this backdrop, there has been a growing body of research, some of it produced by economists at central banks, backing the idea that easier monetary policy tends to be more progressive.

That work, set against the notion that a stricter approach toward containing inflation has the best interests of the lowest-income members of society at heart, is thrusting Fed policy makers toward the center of a debate they usually like to leave to politicians. It’s becoming more contentious as Fed officials seek to declare victory on their goal of maximum employment even while the percentage of prime working-age Americans who currently have jobs is still nowhere close to the peaks of the previous two economic expansions.

George has, since taking the top job at the Kansas City Fed in 2011, been one of the U.S. central bank’s biggest internal critics of low interest rates, but she is not alone on the rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee when it comes to the idea that the Fed must be vigilant about price pressures in order to protect the poor.

Her FOMC colleague Patrick Harker, who became president of the Philadelphia Fed in 2015, argued for the same in January while talking to reporters after a speech in New Jersey, although he was not calling for action at that time.

This is an offshoot of the conventional wisdom shared by the current generation of central bankers around the world. Many economists remember a 1998 study by Christina and David Romer. It concluded that while expansionary monetary policy can reduce poverty in the short run by juicing economic growth, in the longer run everyone will benefit more from policies that aim for low and stable inflation because those measures improve the economy’s overall efficiency.

Although it is true that high inflation in itself can sometimes disadvantage the poor -- the idea is that wealthier people are able to more-easily diversify their savings into assets less susceptible to inflation -- it’s only a small part of the story when it comes to the implications for monetary policy, according to Olivier Coibion, an economics professor at the University of Texas in Austin.

In a recent study, Coibion and his co-authors found that over the period from 1980 to 2008, the inflation-as-regressive-tax argument was swamped by other benefits of accommodative monetary policy that pushed in the opposite direction, leading to a conclusion somewhat at odds with the Romers’ findings.

“Contractionary monetary policy systematically increases inequality in labor earnings, total income, consumption and total expenditures,” he and his co-authors wrote. One notable episode was the early 1980s tightening directed by then-Fed Chairman Paul Volcker, which in seeking to bring down high inflation ended in a severe recession and accounted for “much of the dynamics in inequality” in that decade.

Another recent study published by the Fed itself came to a similar conclusion, but went even further. For “a majority of households” in the study’s model of the economy, the benefits of a monetary policy strategy that focuses more on employment outweigh the associated costs that come in the form of higher and more volatile inflation.

As the Fed has begun raising rates over the past year and a half, there are signs that Fed Chair Janet Yellen may already be rethinking the central bank’s strict focus on inflation, according to John Silvia, the Charlotte, North Carolina-based chief economist at Wells Fargo Securities.

“She has already shifted away from having a very rigid 2 percent target,” said Silvia, who was one of Coibion’s co-authors.

The greater scope for rate cuts that would come from allowing higher inflation would let Fed officials help put people who lose their jobs in recessions back to work quicker.

For decades, there’s been widespread agreement in the economics profession on the overarching merits of price stability as a mandate for central banks. For the Fed, the long period of low and relatively stable inflation helped maintain support for insulation of interest-rate decisions from political pressures.

Ultimately, the Fed may decide to pursue a higher inflation target, but will avoid bringing distributional issues into their reasoning, said Peter Ireland, an economics professor at Boston College.

While some within the Fed have suggested such a course of action is worth thinking about, so far it’s not risen to the level of a serious near-term consideration for policy. Meanwhile, political economy considerations continue to loom large, according to James Galbraith, an economics professor at the University of Texas in Austin.

The biggest threat the Fed faces in Congress is from conservative politicians who have for several years criticized it for holding rates near zero and would like to pass legislation that would amount to greater scrutiny of its policy decisions.

“The argument for doing something about inflation almost always has a strong constituency among the very wealthy,” Galbraith said. “The current situation is one in which the pressure on the Fed is to raise interest rates, and the question is, would they engineer a soft landing by doing so? I think the answer to that is it’s not very likely.”

Article Link To Bloomberg:

0 Response to "Fed Officials Test New Argument For Tightening: Protect The Poor"

Post a Comment