Post-Brexit U.K. Trade Deal With Trump Is Easier Said Than Done

The U.S. president says it can be done "very, very quickly." But economists say, not so fast.

By Jill Ward and Charlotte Ryan

Bloomberg

July 11, 2017

The transatlantic trade deal U.S. President Donald Trump is offering U.K. Prime Minister Theresa May will ultimately prove easy to promise and hard to deliver.

That’s the warning of business leaders and trade analysts after Trump told May last week that the post-Brexit accord she hankers after can be lined up "very, very quickly."

The challenge for the U.K. with talks set to begin this month is that America boasts more leverage and negotiating know-how than the U.K. does. That will potentially force May to compromise on areas such as financial regulation and food standards to land the agreement she needs.

“The U.K. must be absolutely desperate to demonstrate that it’s able to get something from the United States,” said Peter Holmes, an economist at the Trade Policy Observatory, a research group. “The U.S. will make demands that even a desperate British government won’t be able to accede to.”

While the U.K. can’t formally sign deals with other countries until it formally leaves the EU in March 2019, it can prepare the groundwork in the hope of ratifying them soon after. Conversations with the U.S. are set to begin on July 24.

The transatlantic trade deal U.S. President Donald Trump is offering U.K. Prime Minister Theresa May will ultimately prove easy to promise and hard to deliver.

That’s the warning of business leaders and trade analysts after Trump told May last week that the post-Brexit accord she hankers after can be lined up "very, very quickly."

The challenge for the U.K. with talks set to begin this month is that America boasts more leverage and negotiating know-how than the U.K. does. That will potentially force May to compromise on areas such as financial regulation and food standards to land the agreement she needs.

“The U.K. must be absolutely desperate to demonstrate that it’s able to get something from the United States,” said Peter Holmes, an economist at the Trade Policy Observatory, a research group. “The U.S. will make demands that even a desperate British government won’t be able to accede to.”

While the U.K. can’t formally sign deals with other countries until it formally leaves the EU in March 2019, it can prepare the groundwork in the hope of ratifying them soon after. Conversations with the U.S. are set to begin on July 24.

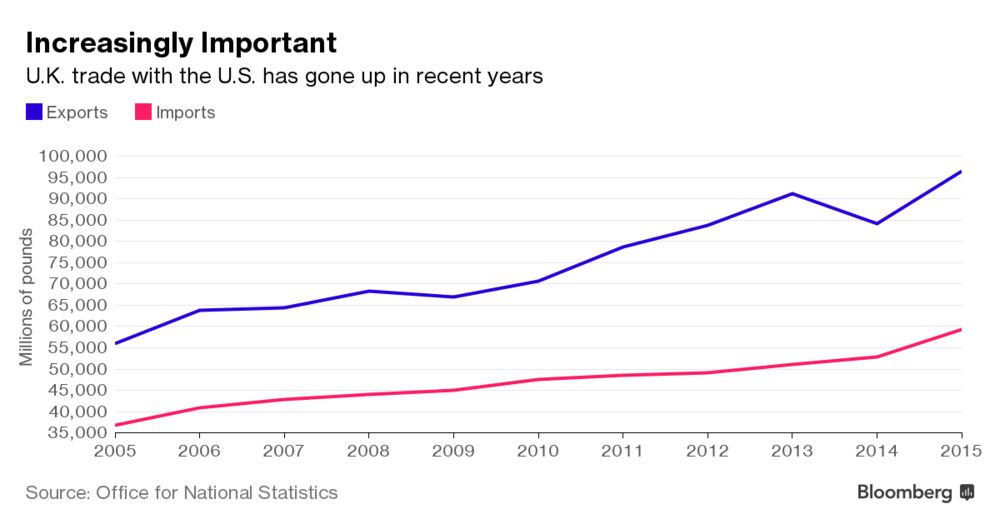

At stake is trade between the U.S. and the U.K, which Britain's statistics office estimates amounted to a surplus 37 billion pounds ($47.6 billion) a year as of 2015. By contrast, the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis calculated a surplus of $11.9 billion in the same year, providing an awkward starting point, with both countries claiming to export more than they import from each other.

“The U.S.A. has one of the best negotiating teams in the world in terms of trade deals,” Paul Drechsler, president of the Confederation of British Industry, a lobby group, told Sky News. “We don’t want to walk into a bear hug and I would be wary of trying to be too fast. A trade deal is a dog-eat-dog activity; it’s not a diplomatic activity.”

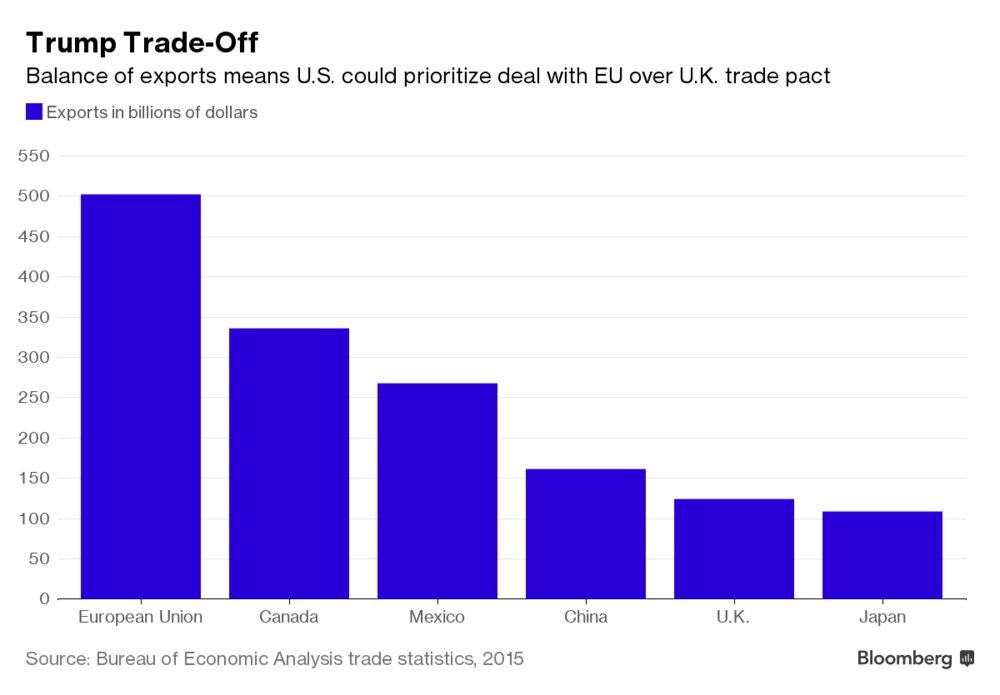

The U.K. may already have a taste of things to come from the inability of the EU and U.S. to agree a trade deal. Those talks have been on hold since Trump took power in January amid differences over data privacy and the rolling back of financial regulations among other issues.

“You’re starting from the same point and the same issues are going to come up,” said Joseph Francois, managing director of the World Trade Institute, a group at the University of Bern.

“There are bigger potential gains from doing a deal with Europe than with the U.K. on its own, just because Europe is a bigger market,” said Thomas Sampson, an economist at the Centre for Economic Performance. “The flip side of that would be that because the U.K. is just one country rather than a block of 27 countries it should have more flexibility.”

The U.K. is already viewing a pact as a way for London-based banks to secure easy access to Wall Street, according to International Trade Secretary Liam Fox. Yet that might require the U.K. to accept weaker rules on finance, less than 10 years after the financial crisis.

Agriculture could also emerge as a sticking point, according to Holmes.

“You can see a Trump administration coming to the U.K. and demanding a loosening of sanitary regulations on food, demanding that the U.K. allow hormone-treated beef to be sold in the U.K. and for the U.K. to accept GM crops,” he said. “There will be quite a reaction against it.”

Another wrinkle could emerge if the U.S. tries to win access for its companies to Britain’s state-run health service. May declined to say in January whether the National Health Service would be off-limits for a trade deal although June’s election may mean she has less room to maneuver on that now.

Still, the effort will be worth it, said Gregor Irwin, chief economist at Global Counsel, a consultancy.

He identified the U.S. as one of the U.K.’s prime targets for striking a deal. He calculated that the total value of U.S. imports expanded faster than those of other major economies between 2010 and 2015 and that although the U.S. has modest average tariff barriers with the U.K., the scale of trade means current barriers are still significant.

Article Link To Bloomberg:

0 Response to "Post-Brexit U.K. Trade Deal With Trump Is Easier Said Than Done"

Post a Comment